Alarming new research indicates that the current policies aimed at limiting global warming will expose over 20 per cent of the world population to extreme and potentially life-threatening heat by the end of this century.

Scientists, publishing their findings in the journal Nature Sustainability, report that Earth's surface temperature is projected to rise 2.7 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels by 2100, pushing more than two billion people, equivalent to 22 per cent of the estimated global population, outside the comfortable climate range that has supported human civilisation for thousands of years.

According to the study, countries most vulnerable to deadly heat under this scenario include India, with 600 million people at risk, followed by Nigeria with 300 million, Indonesia with 100 million, as well as the Philippines and Pakistan, each with 80 million individuals.

Lead author Tim Lenton, the director of the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter, warns that such a situation would bring about a profound reshaping of the habitability of our planet's surface and could necessitate large-scale relocations of populations.

However, the research highlights that capping global warming at the 2015 Paris climate treaty target of 1.5 degrees Celsius would significantly reduce the number of people at risk to less than half a billion, approximately five per cent of the projected 9.5 billion global population in the coming decades.

The study reveals that the rise in global temperatures by just under 1.2 degrees Celsius so far has already intensified the frequency and duration of heatwaves, droughts and wildfires beyond what would have been expected without the carbon emissions resulting from burning fossil fuels and deforestation. Moreover, the past eight years consecutively rank as the hottest on record.

Lead author Tim Lenton emphasises the costs of global warming extend beyond financial measures and the tremendous human toll of failing to address the climate emergency. Lenton adds that for every 0.1 degree Celsius of warming above current levels, an additional 140 million people will face dangerous heat exposure.

The study defines "dangerous heat" as a mean annual temperature (MAT) of 29 degrees Celsius. Throughout history, human settlements have been most concentrated around two distinct MATs: 13 degrees Celsius in temperate regions and, to a lesser extent, 27 degrees Celsius in more tropical areas. As global warming progresses, the risk of surpassing the lethal heat threshold is notably higher in regions already close to the 29-degree Celsius red line.

Persistent high temperatures at or above this threshold have been linked to increased mortality rates, reduced labor productivity, diminished crop yields, elevated conflict levels and greater prevalence of infectious diseases. Just four decades ago, a mere 12 million people faced such extreme heat. Today, that number has increased five-fold and is projected to surge even further in the coming decades.

Regions near the equator, where populations are expanding rapidly, face an elevated risk. In these tropical regions, even lower temperatures can become deadly due to high humidity, which hampers the body's ability to cool itself through sweating. The study also notes that episodes of extreme humid heat have doubled since 1979.

Furthermore, the most vulnerable populations to extreme heat predominantly reside in economically disadvantaged countries with minimal per capita carbon footprints. According to the World Bank, India emits an average of about two tonnes of CO2 per person annually, while Nigerians emit roughly half a tonne per person. In comparison, per capita emissions in the European Union are less than seven tonnes and in the United States, they reach 15 tonnes.

European Commission approves Pfizer's RSV vaccine

European Commission approves Pfizer's RSV vaccine

Two UAE Disney stores to open in March

Two UAE Disney stores to open in March

Abu Dhabi Biobank introduces private cord blood banking services

Abu Dhabi Biobank introduces private cord blood banking services

UAE's Shaikha Al Nowais nominated to lead UN Tourism

UAE's Shaikha Al Nowais nominated to lead UN Tourism

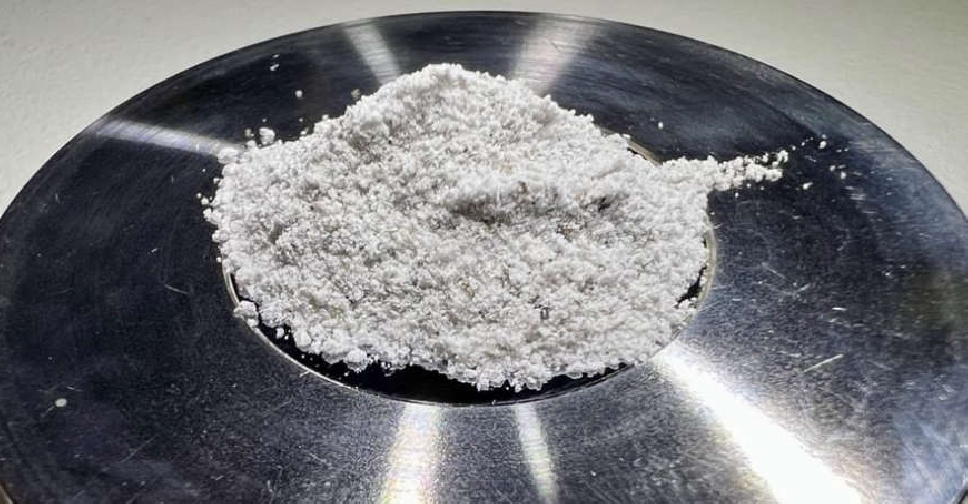

NYU Abu Dhabi researchers develop simulated moon dust

NYU Abu Dhabi researchers develop simulated moon dust