A new study has discovered that the brain's response to nutrients in the gut is impaired in individuals with obesity, and it persists even after weight loss.

The findings of the study published in Nature Metabolism supported a growing body of research that highlights the complexity and enduring biological effects of obesity.

Using brain imaging techniques, researchers observed that when individuals without obesity received nutrients, their brain activity in areas associated with food intake decreased, indicating that it signalled satiety. However, in individuals with obesity, these changes were not detected.

For years, obesity has been viewed as a personal failure to eat less, but there is an increasing recognition that it is rooted in biological mechanisms.

This understanding has led to a demand for new interventions beyond dieting, given its limited effectiveness in achieving long-term weight loss.

Drugs like Wegovy, Ozempic and Mounjaro have emerged to help individuals lose significant amounts of weight.

The study involved 28 participants without obesity (defined as having a body mass index (BMI) below 25) and 30 participants with obesity (with BMI over 30).

To isolate the brain's response to nutrients present in the stomach, the researchers infused tap water (as a control), glucose (sugar) and lipids (fats) directly into the participants' stomachs, excluding any influence from looking, smelling or tasting food.

Initially, the researchers used functional MRI to examine overall brain responses and found reduced activity in regions involved in regulating eating behaviour in individuals without obesity. However, no changes were observed in individuals with obesity. The researchers then focused on specific subregions of the brain related to food intake, known as the striatum, and once again observed decreased activity in individuals without obesity, while no changes were observed in those with obesity.

Subsequently, the researchers employed a different imaging method called SPECT to investigate the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that signals reward from food and plays a role in the motivation to eat. They found that sugar induced dopamine released in both groups, but fats only triggered dopamine release in individuals without obesity, not those with obesity.

To explore the potential correlation between brain responses and gut hormones released during nutrient ingestion, the researchers examined insulin, glucose and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). While no association was found with insulin or glucose, they discovered that in individuals without obesity, higher levels of GLP-1 were linked to reduced brain activity in specific areas involved in food intake after the infusion of fats.

GLP-1 has garnered significant attention in research, particularly due to the popularity of drugs like Wegovy and Ozempic, which mimic the effects of this hormone. Although this study does not delve into the relationship between GLP-1 and brain responses, nor does it explore the impact of GLP-1-based drugs on individuals with obesity, these areas hold potential for future research, according to Serlie, one of the researchers involved in the study.

Two UAE Disney stores to open in March

Two UAE Disney stores to open in March

Abu Dhabi Biobank introduces private cord blood banking services

Abu Dhabi Biobank introduces private cord blood banking services

UAE's Shaikha Al Nowais nominated to lead UN Tourism

UAE's Shaikha Al Nowais nominated to lead UN Tourism

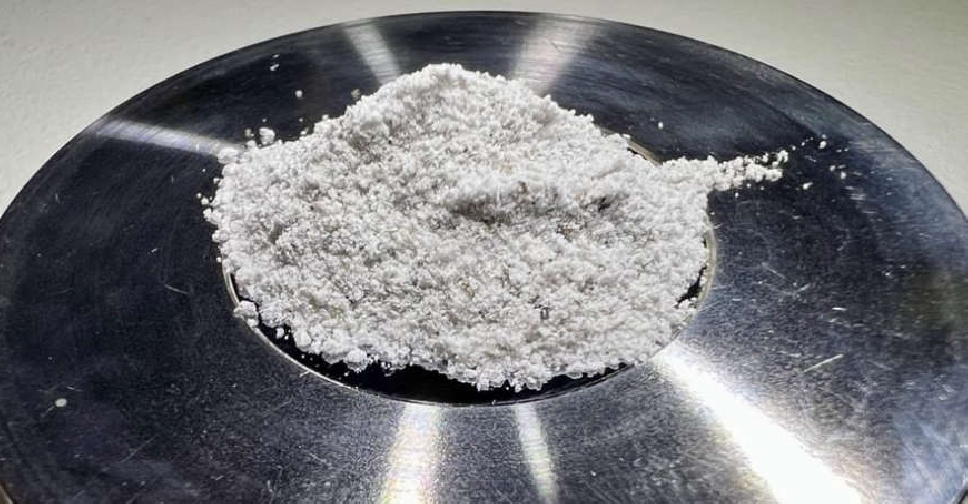

NYU Abu Dhabi researchers develop simulated moon dust

NYU Abu Dhabi researchers develop simulated moon dust

Record 2024 temperatures accelerate ice loss, rise in sea levels

Record 2024 temperatures accelerate ice loss, rise in sea levels